Born to be a leader: Norman Clarke

“As a player, teacher, and coach, what makes me feel really good, is when young people are given an opportunity in basketball, and they experience more than just the game – they express real joy and excitement.” – Norman Clarke

Has basketball been good to Norman Clarke – or has he been good to the sport?

It’s an interesting question. For many, the answer may involve some lengthy analysis and deliberation. Some people simply wouldn’t waste any time and advocate that both are correct.

As a youngster, Clarke was once mesmerized by television shows like the one with an undercover police agent in “Tightrope” or the secret operative thriller “I Spy”. Both had him tinkering with one day pursuing a career as a detective, because he was captivated with the life of a private eye and enthralled with life in a metropolis.

And there was his reference to the word Heaven. It was what he used to describe the city of Toronto when, as an eight-year-old, he arrived in Canada. He had come from his native Jamaica, where home was in a place called May Pen, viewed as one of the country’s most important agricultural towns.

Clarke absorbed everything – watching from the skies above on his first plane ride and seeing miles of bright lights. Then, after he had landed, the cleanliness of streets and a wealth of freshness. To him, it was paradise – and he would need time to adapt to this place he called a dreamland.

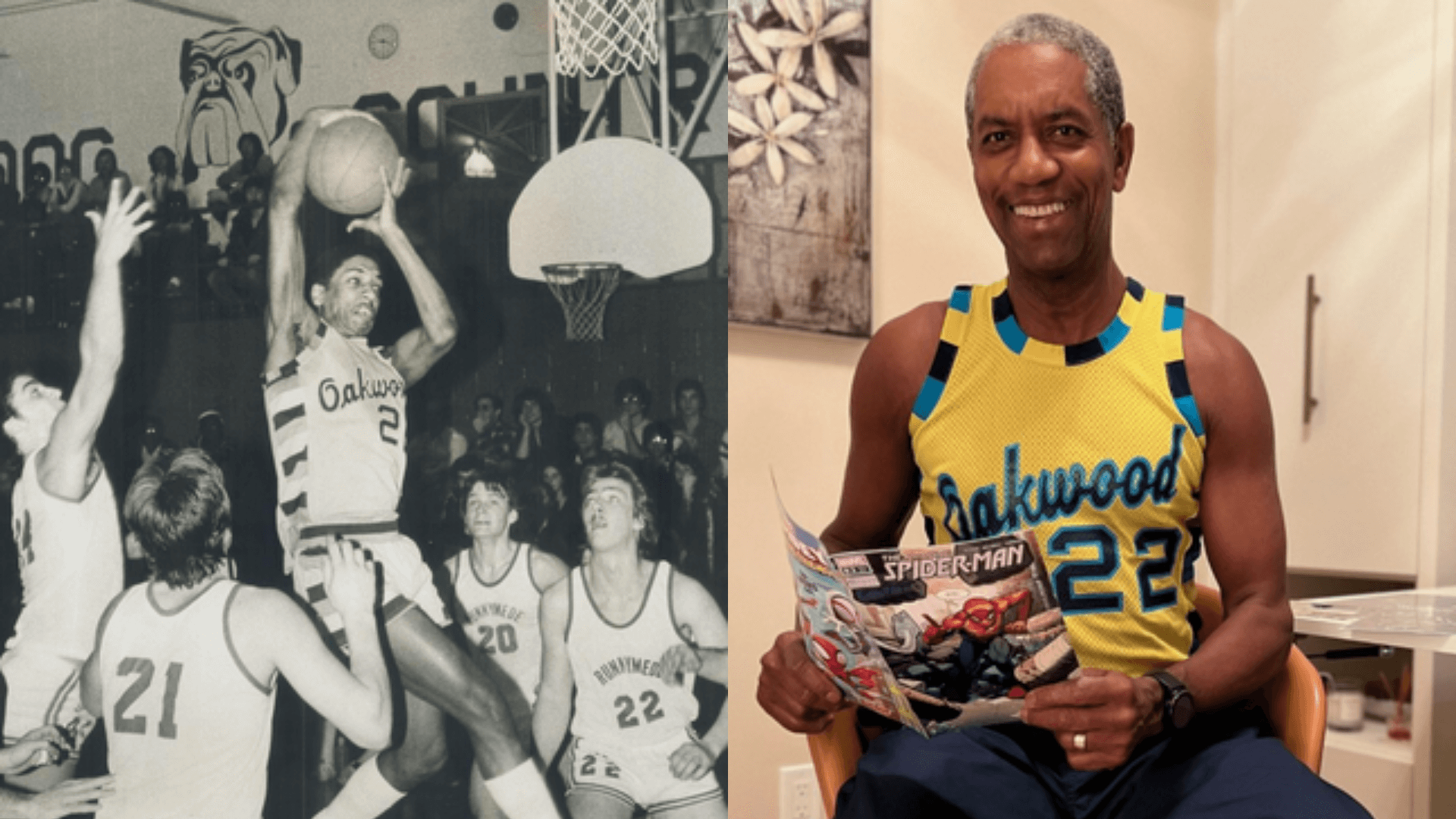

The youngest of three siblings, Clarke had a flair for things. Sports, like the one which may mention a target quiver, was, and still is, high on the list. But, as a 12-year-old, his interest focussed on – comic books. It had become more than a hobby as he put together a collection of action thrillers. Today, Clarke has accumulated more than 24,000 comics – the majority are of the superhero nature.

For people who have only linked Clarke’s name to just basketball, well, there’s more to his life. He was always fascinated by his grandmother’s baking. In his late 20s, Clarke chose to study food prep, and went on to earn a diploma at Toronto’s George Brown College. He would even do a few shifts at Joe Allen’s – the classic neighbourhood bistro and Broadway institution. It was around the time that he attended St. Bonaventure University, located about one hour from Buffalo in upstate New York.

Had enough? Read on.

Education has always been important to Clarke. There were the days he was a student – to a 30-year career as a teacher with the Toronto District School Board. Coaching was also a high priority. He would find time to do both for three decades – and all at Carleton Village Junior and Senior Public School. There were also plenty of basketball championships, too.

Thinking about his past, Clarke recalled some interesting and challenging times.

As a youngster, he attended three elementary schools – Clinton, Dewson, and Kent. After that, it was on to the secondary system starting at Western Technical and Commercial School. That didn’t last long, and he was off to Oakwood Collegiate, a school known for excellence in basketball. That’s where he would later earn the title of Athlete of the Year and take that memory along with his graduation diploma.

Things didn’t work out at Clinton because of what he called concerns related to racism. Clarke said people had made fun of his Jamaican dialect and was the subject of constant ridicule. He feared for his safety, too, and chose to switch schools. Then, as a teen at Western Tech, again the negative racial vibes directed at him because of the color of his skin.

“Oh yes, there were serious racial problems back then, too,” said Clarke, in a conversation where he shared his understanding and realization of the times. “Things became much better when I went to schools with more visible minorities. It was very different – and I felt accepted.”

Very involved in ball hockey, basketball would quickly take over his life. It happened as a 10-year-old when he signed up for an after-school program that took place at Central High School of Commerce.

“I liked (basketball) a lot and in the summer would practice, learn to dribble and improve my shooting technique,” said Clarke, who also shared an unfortunate situation that set back his basketball playing time.

A race through a school hall ended with his right hand going through a door window.

“I was 11 years old, had 30 stitches and it was not a nice time,” he said. “I had to sit out, wait for everything to heal – but also learned how to dribble with my left hand.”

Clarke would go on to excel and helped Dewson win the city championship for students in Grade 6. Two years later, again he was a leader as Kent went on to claim city bragging rights. As a point guard, he was also the top scorer at both schools.

“I can remember once sitting with friends watching the 1972 Olympics and said that one day, I wanted to be strong, big and good enough to play at one of those events,” said Clarke.

“Basketball was very good to me. It kept me away from the wrong crowd, insulated me and I saw that Black people respected me and gained confidence in what I was saying and doing.”

Those who followed his rise to fame, would see the best was yet to come for Clarke. His commitment to the sport and love for the game was second to none. The game inspired him to strive for success.

While at Oakwood, Clarke was on teams that dominated opposing schools and capped three seasons as the best in Toronto. Back then, I had chosen him on my annual Toronto Star high school selection of the top five players. Clarke was that good.

He made Canada’s Junior National team at age 18. Scholarship offers flowed in from National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) schools. Clarke would settle on St. Bonaventure and was one of the few Canadians at the time, that hit the big USA stage. But he wasn’t finished.

It was at the age of 23, thinking about being drafted into the National Basketball Association, when Clarke broke his jaw at a summer tournament. His jaw was wired shut and he was frustrated. Again, it was time to take a breather from a sport he adored.

“Basketball was the world to me,” recalled Clarke, who had graduated with a university degree in marketing and, at the age of 28, he was about to realize that his Olympic dream from those early years would become reality.

“I was on the 1988 Canadian Olympic team that played in Seoul (South Korea). There was adversity, and I had my share, but I didn’t quit. I did my best, saw there were challenges being a visible minority, and I had trouble dealing with the situation at the time.”

Despite years of hard work, grit and unwavering support, Clarke had found a form of success – but it was also a moment of truth-seeking. He would also go on to graduate from Teachers College at the University of Toronto.

The accolades would continue to pile up, including his induction to the Ontario Basketball Hall of Fame. It was also a matter of time before his competitive days would end and he would focus on another aspect of the game – coaching.

“I started a program 20 years ago, because I saw an opportunity that would help kids in the community, teach them skills and how to play the game the right way,” said Clarke, who is President, club coordinator and a coach of the Toronto Triple Threat Basketball Club, which caters to inner-city boys and girls between the ages six to 18.

“As a player, teacher, and coach, what makes me feel really good, is when young people are given an opportunity in basketball and they experience more than just the game – they express real joy and excitement.”

-END-

David Grossman is a veteran multi award-winning Journalist and Broadcaster with some of Canada’s major media, including the Toronto Star and SPORTSNET 590 THE FAN, and a Public Relations professional for 50+ years in Canadian sports and Government relations.